When I was in school, I thought I knew what I wanted to be in life. I had a few options, with the little I had seen growing up:

1. A catholic priest

2. A rockstar

3. A doctor

I pursued the first early on, found the second to be ‘unfeasible’ and gave up option 3 in junior college when I couldn’t prick my own finger in the lab for a blood sample. I had chosen science after high school, and later on graduated as a math major. I really liked math; I wasn’t bad at it, but not really good either.

While the work I do now isn’t heavily informed by my math degree, it benefits from the blend of experiences that I have had in my life. Math was probably not the best choice for me, but my love for learning kept me in touch with lot of other knowledge and opened me to a whole lot of other experiences. These (including the beauty of math!) are experiences I am grateful for and from which I draw in ways that I cannot clearly explain.

Many students are preparing themselves for life after high school. Many parents have plans for their children. Looking back, I wonder if choices could have been simpler and easier after high school. I wonder if I could have had a test trial of the choices that I had had before me.

I now wonder if it is time to break the walls between these choices. In a world as complex as ours, what kind of lenses are being provided to young students to engage with the world?

The boundaries need to be challenged.

Going Greek: The Roots

A little unlike the MPs we have today who represent (or misrepresent) people in Parliament, ancient Greece had direct representation i.e. free people took active part in civic life, from vociferously debating issues through argumentation and conversations to showcasing a defence in court. The risk of not being reasonably good at this was understood – one wouldn’t have their needs met or have their rights upheld.

So at the base, the Greeks learnt the trium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric) while the quadrivium (arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy) was important secondary education. Together, these came to be known as the liberal arts. Today, the scope of a liberal arts education has widened to include fields of contemporary relevance. The goal is to develop skills with a comprehensive view of the world and where it is heading.

I am not suggesting a simplistic replication. But I am inquiring into ways of dealing with a trium that exists in India.

The Indian Trium

Most students choose one of these pathways after high school:

Arts. Science. Commerce.

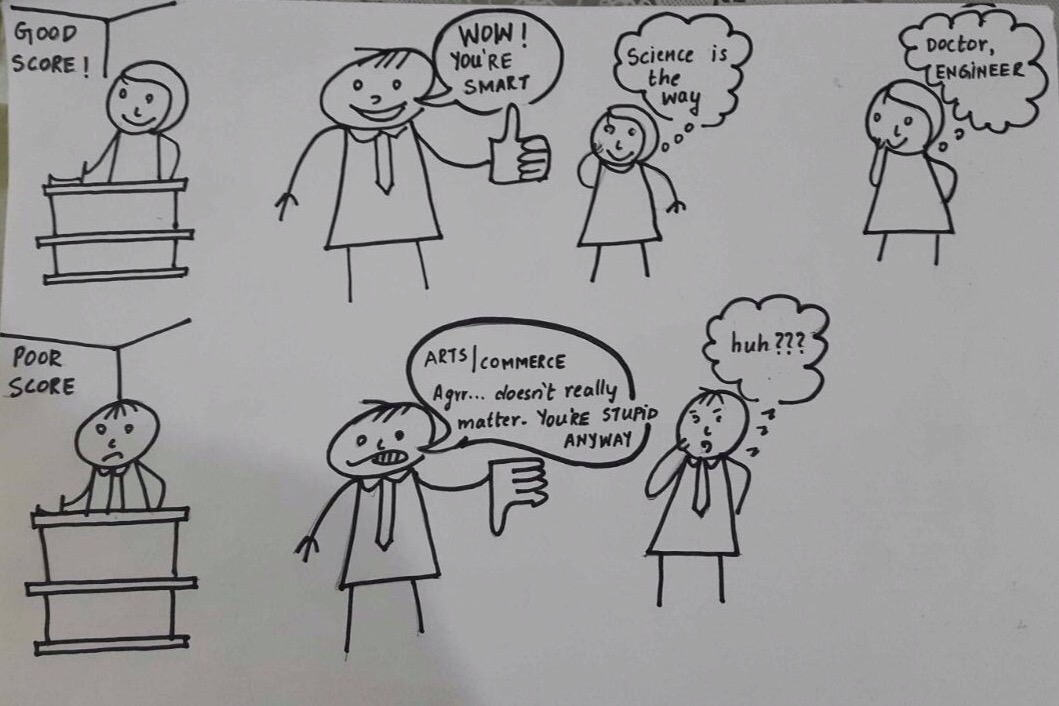

I could expend a few words OR I could drive home a traditional view with a simple illustration:

So the underlying assumption is that your high school score qualifies (or disqualifies) your aptitude AND your intelligence for a particular kind of study.

(Generalizations, though unfair, have been used to only highlight a dominant mentality)

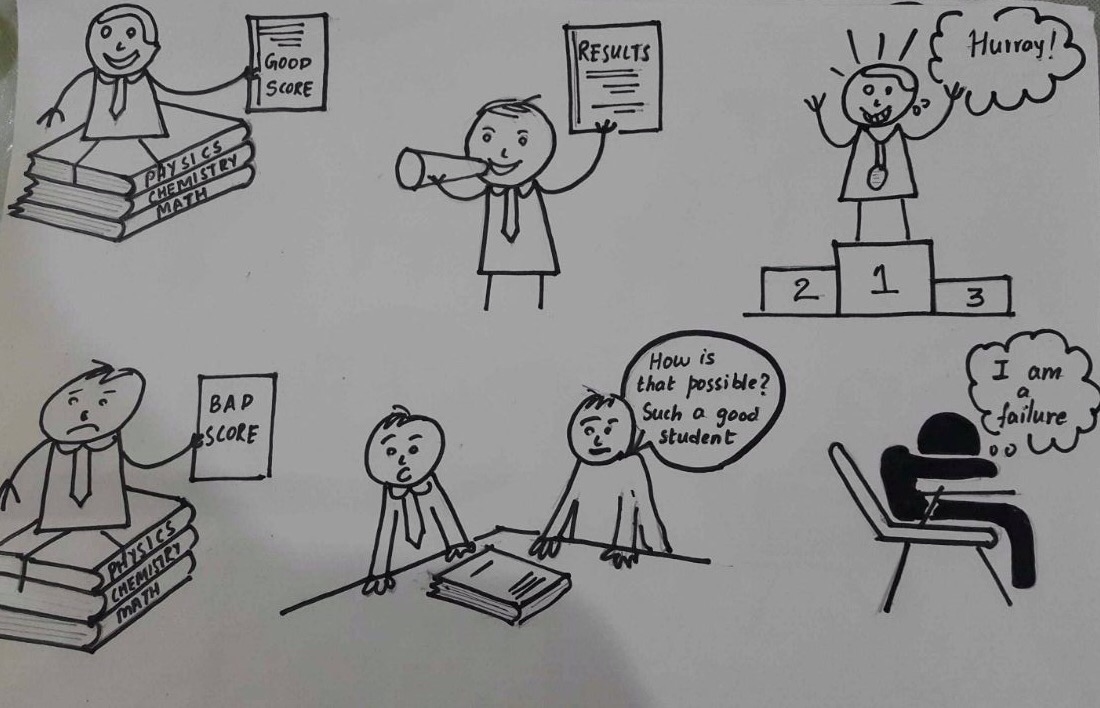

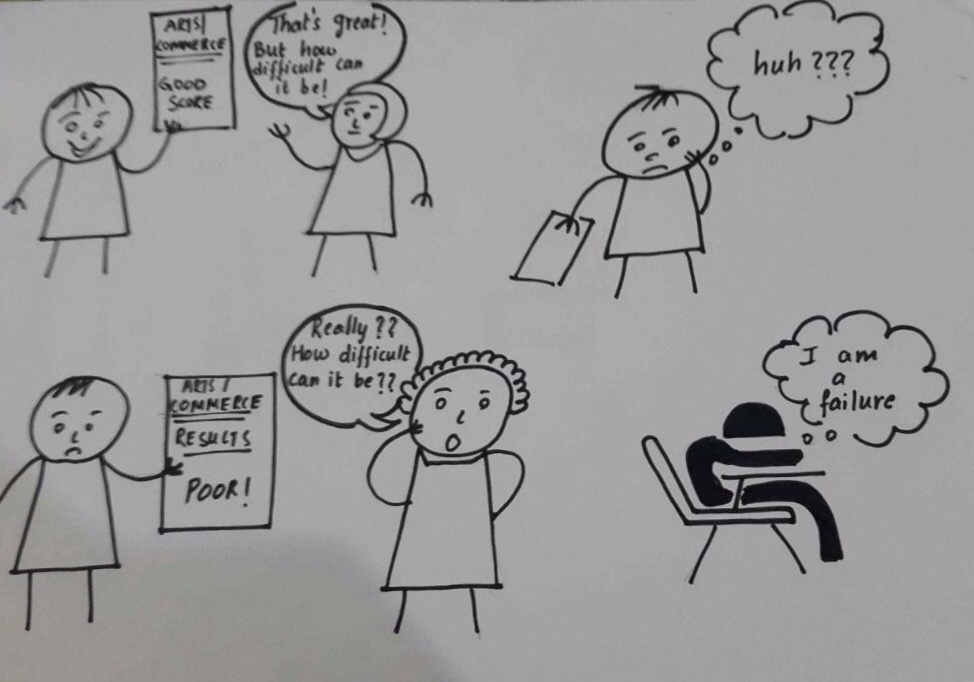

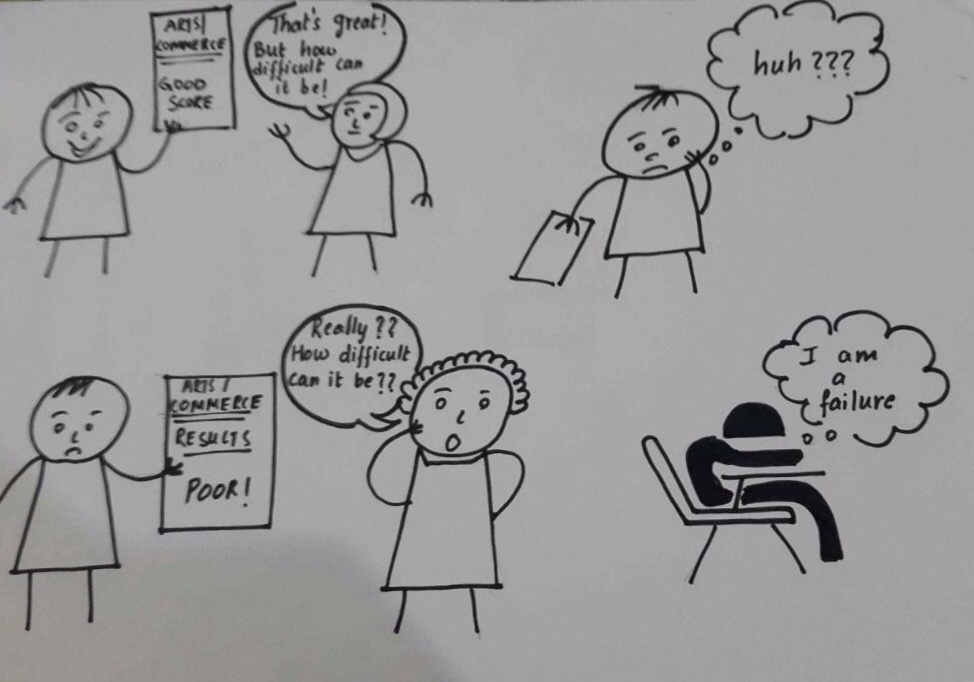

The ones who are mildly insulated from such darts are the ones who score well, those who have a genuine proclivity for a stream they have chosen and others who have a determination to get good scores. These we call the Toppers.

There are those who do neither too badly nor too well. This is the OK Gang. They get scores which are satisfactory from the teacher’s viewpoint but mildly relieving or dissatisfying (or both) from a personal one.

The students who perform poorly are a worry for everyone – they are the Problem Kids.

So now we have 3 groups:

1. The Toppers

2. The OK Gang

3. The Problem Kids

Growing up, most students subconsciously know where they belong.

Take into account teacher perceptions, cultural biases, family attitude, peer pressure, etc. and we soon have a dangerous concoction. Not only do many students fail to discover the joy of learning, but they breed fixed mindsets that are personally damaging. People forget scores, life happens, but these mindsets and attitudes stick to the self.

The problem doesn’t lie merely in a seemingly appropriate or inappropriate choice of stream, but how such a choice makes us define ourselves and others.

Why go beyond compartmentalization?

At a simple level, this has a simple answer – students must get to test all waters before making a deep-dive choice.

Can we afford to not consider a better, integrative education?

Education and the Market

Market forces are everywhere, and education is no stranger to it. The dominant belief seems to be that the purpose of a ‘good’ education is to get you a job better than the one you would get with a ‘lesser’ education. This usually means a rush for streams and courses that are currently in vogue and which could lead to lucrative opportunities in the future.

For too many people, the relation between education and the market is as simple as:

Very educated —> Top Job

Well educated —>. Good Job

Poorly educated –> Poor Job

The problem? Things are never that simple. We fail to consider a host of other factors beginning from the personal to the sociopolitical.

In India, the market mindset is rarely challenged in education, which is why traditionally, a well-paid job has been the singular goal of education for most people, and rightfully so in a country with deep inequalities. Things are changing slowly, but market forces tend to dictate heavily what kind of an education would offer a good return on investment (Indian students joining STEM being a case in point), but they are not future proof. What is future proof are the insights and skills that a person has in navigating unpredictability and uncertainty.

While students build competencies for the market, they must also build competencies to question and challenge market dynamics. A simple look at innovators in all fields over the centuries tells us that disruptive ideas go beyond the confines of existing structures, forces and expectations. This happens best in an ambiance of deeply engaged and connected learning.

It is not Personal vs. Professional

For too many of us, getting educated for its intrinsic value is pitted against getting educated for a well-paying job (something Lisa Dolling calls a false dichotomy in this wonderful piece). Growing up, this has been a double headed issue that has gotten some seriously lopsided attention.

Education’s role as a ticket to a well-paying job is in conflict with our pursuit of education for its inherent, intrinsic values. Many of us (including me) were conditioned to perceive education for merely professional ends but were rarely actively encouraged to relish the joy of learning. I think we are missing out on a lot of goodness if we look at educational goals, in practice, as mutually exclusive. Creating a space for students to discover joyous learning is an opportunity we must not consider affordable to miss out on.

The Potential

Ambitious projects launched under the Skill India initiative aim to train over 400 million people in India in different skills by 2022. Financial rewards for candidates who successfully complete the approved skill training programmes have been planned under the flagship scheme. Skill India maybe a great short term fix for a country in which education hasn’t had the transforming effect it should have had and wherein budgetary allocation for education are eroded by inflation and GDP growth rate. We are talking about a country that is slated to have the highest student population by 2025.

Providing monetary incentives for skill training still reflects a strong market-driven approach. The bigger question we need to ask is, what are we accomplishing or ‘buying’ with long term monetary incentives? Who is being truly served? I am just scratching the surface here.

Consider this definition of education of Steven Pinker, which I have reproduced here in its entirety because it is worth reading:

“It seems to me that educated people should know something about the 13-billion-year prehistory of our species and the basic laws governing the physical and living world, including our bodies and brains. They should grasp the timeline of human history from the dawn of agriculture to the present. They should be exposed to the diversity of human cultures,and the major systems of belief and value with which they have made sense of their lives. They should know about the formative events in human history, including the blunders we can hope not to repeat. They should understand the principles behind democratic governance and the rule of law. They should know how to appreciate works of fiction and art as sources of aesthetic pleasure and as impetuses to reflect on the human condition.”

“On top of this knowledge, a liberal education should make certain habits of rationality second nature. Educated people should be able to express complex ideas in clear writing and speech. They should appreciate that objective knowledge is a precious commodity, and know how to distinguish vetted fact from superstition, rumor, and unexamined conventional wisdom. They should know how to reason logically and statistically, avoiding the fallacies and biases to which the untutored human mind is vulnerable. They should think causally rather than magically, and know what it takes to distinguish causation from correlation and coincidence. They should be acutely aware of human fallibility, most notably their own, and appreciate that people who disagree with them are not stupid or evil. Accordingly, they should appreciate the value of trying to change minds by persuasion rather than intimidation or demagoguery.”

Along with provisions for technical skills and a space to explore interests, we need to look at our myriad cultures, appreciate the goodness and immense human spirit they embody. We also need to be critical and mindful of what our cultures represent and its implications on people who do not share the same beliefs.

In the face of growing intolerance, education must help us celebrate our cultures while also developing empathy to find common grounds.

Update (30 April, 2020)

I have had to revise some of the ideas I have shared here; education can be pursued for its intrinsic values and for professional ends but I think it is heavily contingent on the foundational aspects of a particular school system and the participants it inadvertently includes or excludes. Ideally, the personal-professional should be a false dichotomy but it isn’t in practice. There is a lot to unpack here and I might pick this up in the future.

Be First to Comment