There has been a global boom in the growth of philanthropic institutions over the past 25 years. Interestingly, there has also been a steady rise in global inequality, both between and within countries. Having worked in diverse capacities in the education and development sectors in India over the past 8 years—sectors that have many philanthropic institutions as their driving force—I was curious about the relationship between philanthropy and inequality in India.

One of my course assignments gave me the right opportunity to delve deeper into this issue. More importantly, it helped me critically reflect on philanthropy and the social impact space during a time of political turbulence.

Let us first consider a more general but key question: how are philanthropy and democracy connected?

Philanthropy and Democracy

We can break the above question at the very least into a couple more:

- How compatible is philanthropy with values like liberty, equality and social justice?

- What are the limits (and dangers) of philanthropic power?

Indeed, we are challenged regarding compatible values, benefits, and who gets to define them for philanthropy within a democracy. A key facet of democracy is the commitment to political equality so that citizens have equal opportunity for political participation and influence and are recognised as equals in the public domain. A consequence of this principle is that when socioeconomic inequalities are exacerbated, a democratic society’s commitment to political equality is threatened. Therefore, both the political process and the tangible outcome of solving inequality matter in a democratic society.

It is difficult to deny that private philanthropy’s attempt to define and solve inequality is an exercise of private power and it intersects, interacts, and interferes with functions of the state and the market. The evolution of philanthropy into the forms we witness today is inextricably tied not only to the evolution of states but also to the evolution of markets which are increasingly financialised and globalised.

The other key phenomenon that is also tied to the evolution of the state and the market is inequality.

A brief view of global inequality

Since the financial crisis, the number of billionaires has almost doubled. In 2018, billionaires together increased their wealth by nearly $2.5 billion a day. On the other hand, the rate of poverty reduction has nearly halved since 2013, despite the usage of a poverty line that many scholars argue is too low. The World Inequality Report 2018 notes that the wealthiest 1% of the population in the world ‘captured twice as much growth as the bottom 50% individuals since 1980’ due to the rising inequality within countries.

Through his work, Piketty has shown that on average, the return on capital tends to be greater than the rate of economic growth. Therefore wages—which most people (including me) depend on—fare poorly in comparison to returns on capital that are accrued by a few. The disproportionately high ownership of capital by the private sector has been a significant driver of inequality. Since 1980, there has been a massive transfer globally of public to private wealth (except oil-rich countries like Norway). With such diminished public wealth, the ability of governments to tackle inequality gets eroded.

Effective use of public revenue by way of taxation can be highly instrumental for governments in addressing some of these issues.

A small note on (how) tax matters

Taxation—and more specifically, progressive taxation—can be effective in curbing inequality. Progressive tax rates reduce both pre-tax and post-tax inequality and provide fewer incentives for top earners to accumulate wealth. But on a larger scale, the reality is that economic policies and policy instruments could be guided by ambiguous norms and values that affect how they are implemented and impact economic growth and inequality.

Therefore, though taxation is an important instrument for meeting economic goals, how it is structured depends on how the goals to be achieved are defined (or understood) and whether the trade-offs by politico-economic decision-makers are considered feasible. A greater reliance on progressive direct taxes can lead to a more equitable income distribution but it might also have a negative effect on the rate of economic growth.

Why am I talking about this? Because our collective understanding of issues like inequality, economic growth and governance matters in understanding how instruments like taxation work— or fail to work—for everyone. I shall come back to tax discussions later.

Case Study – India

(While there has been a tremendous rise in the development sector in India, there is no integrated data available on institutions based on categories, funding partners and investors. In this piece, I mainly rely on the India Philanthropy Report (IPR) started by Bain and Company in 2014, one of the few annual studies undertaken to gauge the pulse of the philanthropic sector in India.)

The concept of giving is hardly a unique one in India—a complete chapter is dedicated to charity in the ancient Hindu scriptural text of the Rigveda. More organised institutional structures for giving emerged in the 18th century with the establishment of the Societies Registration Act under British rule in 1860. Few of the big Indian industrialists set up their philanthropic foundations before the Indian independence in 1947. The Companies Act 2013, a follow up to the Companies Bill in 2011, made Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) contributions mandatory for large firms with net profits over approx. $750,000. Such firms would have to spend 2% of their annual profits averaged over three years on CSR activities.

In the latest IPR 2019, the combined CSR budget outlay for domestic corporations and contributions of corporate charitable trusts had grown at 12% between 2014 and 2018. In 2018, they contributed over approx. $1.8 billion to the social sector. 60% of CSR projects were in the fields of health and education. But a major proportion (60%) of private funding is provided by individual philanthropists, estimated at around approx. $6.08 billion.

While the government was still the largest contributor to the social sector, the rate of private philanthropy outpaced that of public funding over the past 5 years. IPR provides little clarity on whether the social sector includes both non-profit activities and for-profit social enterprises. Based on my own professional experience, it includes both non-profit activities organisations and for-profit social enterprises focused on providing public goods and services. (if you know better do reach out to gently correct me).

Despite governmental efforts and philanthropic activity, IPR estimates there will be a shortfall of $60 billion annually needed to achieve at least 5 of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The 2018 report suggests that leaving aside a few exceptions, ‘individual philanthropists are contributing two to three times below their giving ability and need to do more’. In IPR 2017, there is recognition of the fact that the number of ultra high net worth individual (UHNWI) households doubled since 2011 and during the same period had their net worth tripled. The report attributes a greater rate of philanthropic activity to better performing economic macroindicators that have led to a rise in UHNWI households.

Therefore, while the number of UHNWIs has increased and the rate of philanthropic giving has increased over the past 5 years, there is a lot more scope for UHNWIs to give more. The shortfall and the growing number of UHNWI households indicate a widening inequality in India.

Tracing economic growth and inequality in India

The liberalisation of the Indian economy in 1991 was accompanied with the implementation of structural adjustment programmes as required by the International Monetary Fund. Funds flowed into the economy but were not equitably distributed; investments into the corporate and financial sector increased while many small enterprises failed to attract investments they needed to thrive. Investment in manufacturing and in the provision of public goods like health and education were also decreased.

While liberalisation—and later, globalisation—led to steady improvements in macroindicators like GDP, they not only led to capital accumulation but also affected the labour market leading to more inequality.

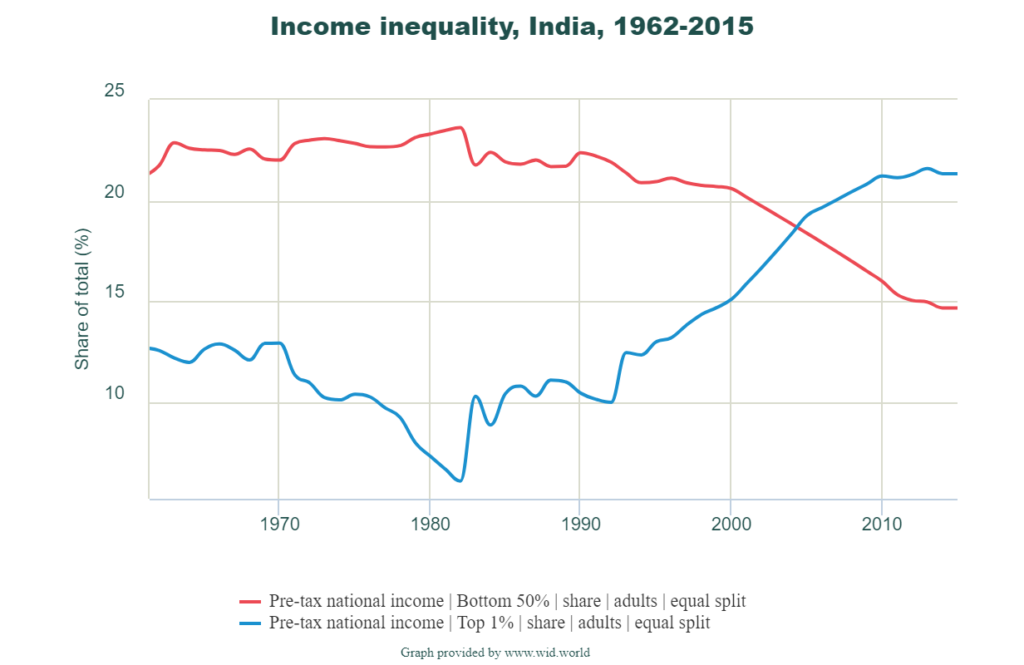

If we consider data from the World Inequality Database, there has been a sharp increase in the share of total national income of the top 1% of the population right through the 1990s and the early 21st century. This growth has been accompanied by a corresponding decrease in the share of the bottom 50% of the population.

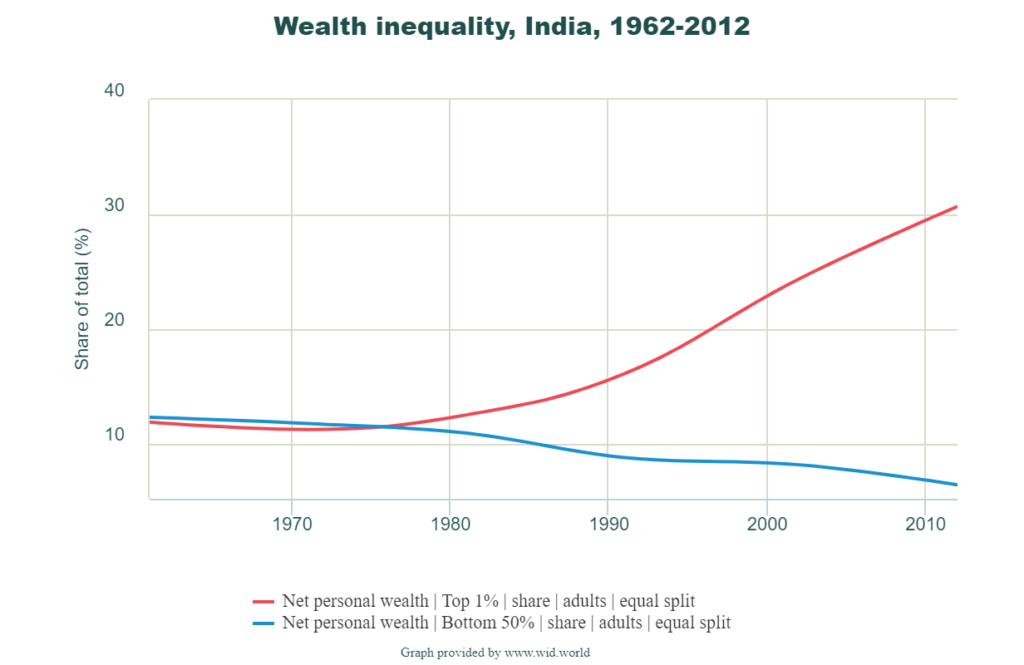

The graph for wealth inequality also indicates a growing disparity about the same period between the share of wealth held by the top 1% and the bottom 50% of the population (Figure 2). The Gini wealth coefficient has risen from 81.2% in 2008 to 85.4% in 2018. While the total national wealth increased by $151 billion in 2018, the top 1% increased their wealth by 39% while that of the bottom 50% increased by only 3%.

The disparities in both income and wealth makes the quality provision of public health and education services important functions of a democratic society.

In India, while government spending on these two public goods has remained at about the same level, there has been a steady growth in the private health and education sectors. The government spending on health has hovered around 1.3% while the global benchmark is 3.5% of GDP. According to the World Bank, there were only 0.7 doctors for 1000 people in India in 2012. Both China (1.8 doctors per 1000 people) and the United Kingdom (2.8 doctors per 1000 people) fare better on those indicators. The contrast in the quality and provision of health services for the many and the few is reflected in the fact that while India ranks 5th on the Medical Tourism Index (because of relatively cheaper provision of high-quality health service by the private sector), it ranks 145th in a ranking of 195 countries for quality and accessibility of healthcare.

Similar dynamics are in play for education—government spending has been around 4% of GDP while the global benchmark is 6% of GDP. Private schools enrolled 17.5 million new students while enrollment in government schools fell by 13 million across 20 states between the academic years 2010-2011 and 2015-16.

The data indicates that along with the rise in inequality, the rise in provision of health and education services by the private sector has accompanied the decline in the provision of these services by the Indian state.

In such a reality, what do we make of the impact of philanthropy on inequality in the Indian context?

Conclusion

Based on the data I have considered from recent years, the nature of the effect of private philanthropy on economic inequality in India is unclear and the evidence of a positive effect is scant. Moreover, how philanthropy and the state effectively interact in the provision of public goods and services is also unclear and there is a lot more collaboration needed to make that picture clearer. While the rate of philanthropic activity has greatly risen over the past 5 years, coupled with the current quality and rate of government spending on public services, it might not be enough in meeting the funding shortfall to achieve key development indicators.

It is difficult to statistically isolate and explore the causal effect of private philanthropy on inequality in India especially within the limits of a short research piece. A more bothersome issue to consider is the possibility of reverse causal effects: does the rising inequality enable more ultra high net worth individuals to engage in private philanthropy? The analysis of both these causal concerns are, I believe, exciting opportunities for cross-sectoral and interdisciplinary research and practice.

Reflections on philanthropy, state and the market

Taxation policies can be indicative of the weightage given by a state to the distinct goals of economic growth and income inequality. India greater reliance on indirect taxes (which is more burdensome for the poor) than direct taxes reveals a preference for economic growth over income inequality. Together with the other factors discussed earlier, inadequate government spending on public goods and regressive taxation policies could widen inequality.

Recent research shows that when philanthropy engages in increasingly popular market-based models like social enterprise and entrepreneurship for the provisioning of public goods, it could encroach and undermine political strategies used in democratic societies to achieve social justice goals. Private philanthropy, in such a context, can exercise more power through market forces in defining and providing public goods and services. A growing dependence on such philanthropy threatens democratic equality. This is something that demands a larger public engagement.

But philanthropy is far from being undesirable and unimportant today. Looking at the bigger picture, the question we ought to collectively think about is how best can philanthropy—and by extension, the social impact space—tackle inequality, especially when democracy is in crisis?

Thinking out loud

In conclusion, based on my research, I’d like to brainstorm a few ideas that might be helpful. (The assumption I am making is different stakeholders may collectively discuss these ideas without compromising democratic principles)

Reparative, deliberative philanthropy: Under the non-ideal realities of current democracies, philanthropy can be viewed as a principle of reparative justice. Instead of relying on the donor’s personal interest and opinions on social benefits, private philanthropy could be directed at solving some of the biggest social issues in our society. There could be a deliberative, public-private consulting body that advises philanthropists on the best use of funds (the caveat is that such a body should not be prey to regulatory capture). Such collaborative philanthropy could also be encouraged by tax incentives that are disproportionately eclipsed by public returns on the philanthropic social interventions.

Political action and social policy entrepreneurship: In order to hit at the root causes of inequality, philanthropic funds could also support grassroots political advocacy organisations that promote values grounded in democracy and social justice. Bad politics threatens democracy and positive social impact—the power of positive political action is something serious philanthropy might want to reflect and consider. Robert Reich, an expert on philanthropy, suggests that an interesting function of philanthropy could be in driving social policy entrepreneurship. Because governments are risk-averse at experimenting with social policies because of the fear of electoral backlash, philanthropy could support testing such experimental policies in an ethical manner with conscientious democratic leaders at various national and sub-national levels.

Progressive taxation: Apart from the philanthropic approaches above, a progressive tax policy alone can be a very effective tool in fighting inequality, assuming it can be well implemented. This could also be accompanied by strategies to thwart tax evasion and abolish tax havens, something that will need international cooperation and accountability.

How has this piece got you thinking? What do you disagree/agree with? What are the perspectives the author has failed to account for? Do comment and share your feedback.

References

2017 | Indian Philanthropy Report Bain and Company, Inc.

2018 | Indian Philanthropy Report. Bain and Company, Inc.

2019 | Public Good or Private Wealth: The India Story. Oxfam International.

2019 | Public Good or Private Wealth? : Oxfam International.

ALVAREDO, F., CHANCEL, L., PIKETTY, T., SAEZ, E. & ZUCMAN, G. 2018 | World Inequality Report 2018. World Inequality Lab.

FOURCADE, M. & HEALY, K. 2007 | Moral views of market society.

GIRIDHARADAS, A. 2018 | Winners take all : the elite charade of changing the world.

HICKEL, J. 2018 | The divide : a brief guide to global inequality and its solutions

JOHNSON, P. 2018 | Global Philanthropy Report – Perspectives on the global foundation sector.

LINDAUER, D. L. & VELENCHIK, A. D. 1992 | Government Spending in Developing Countries: Trends, Causes, and Consequences.

LIU, Y. & MARTINEZ‐VAZQUEZ, J. 2015 | Growth–Inequality Tradeoff in the Design of Tax Structure: Evidence from a Large Panel of Countries.

MARX, K. 2012 | The communist manifesto : a modern edition

MAZUMDAR, D. 2008 | Globalization, labor markets and inequality in India

MCGOEY, L. 2016 | No such thing as a free gift : the Gates Foundation and the price of philanthropy

PIKETTY, T. 2014 | Capital in the twenty-first century

REICH, R., CORDELLI, C. & BERNHOLZ, L. 2017 | Philanthropy in democratic societies : history, institutions, values

Be First to Comment